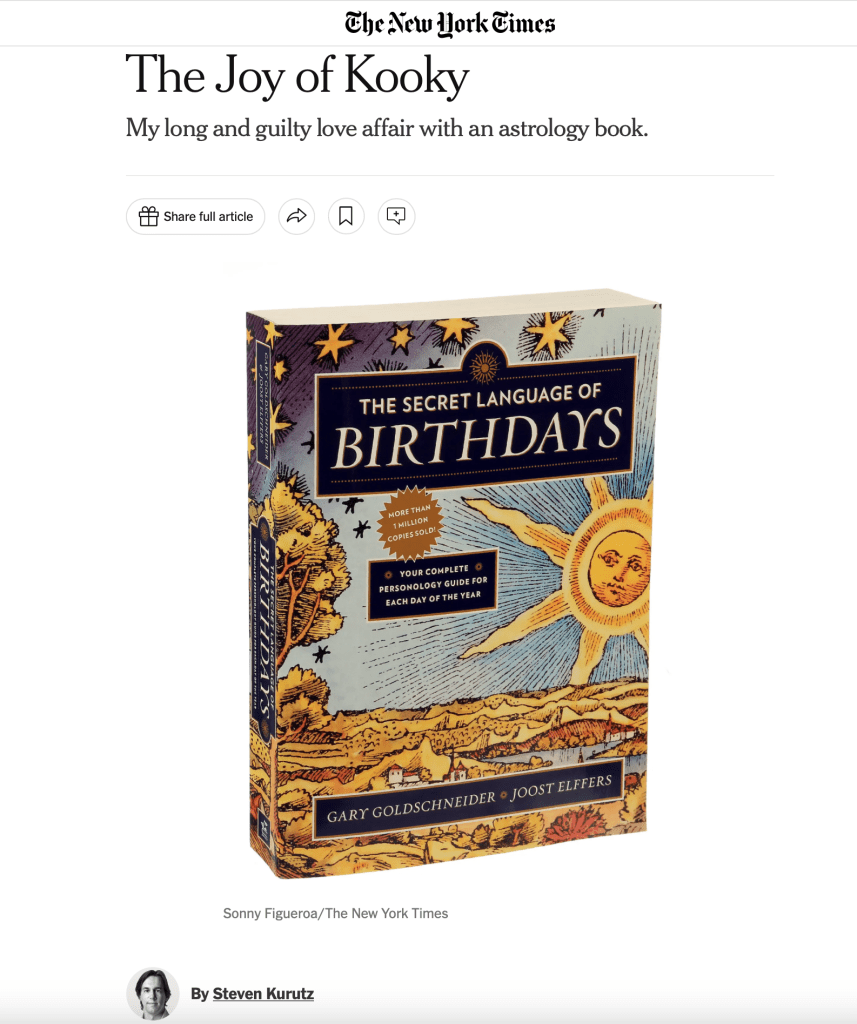

The Secret Language of Birthdays

More than 30 years ago I helped my father—the author, composer, and pianist Gary Goldschneider—write and bring to fruition The Secret Language of Birthdays, the best-selling coffee table book of all time, which is still in print today, has sold millions of copies, and been translated into more than 12 languages. The book’s producer, Joost Elffers, guided the book’s look and presentation, helping to make it a success.

This highly accessible astrology book, which only requires one to know the day of the year on which one was born, was an instant hit, as people would begin by generally looking up their day in the bookstore, and then move on to family, close friends, romantic partners . . . and would soon bring the book home with them, where it would become a conversation starter at parties and bring people together in discussing their personalities. Libraries could not keep it in their collections, as it was invariably stolen.

Below are some excerpts from a New York Times article by Steven Kurutz on The Secret Language of Birthdays (written after my father’s passing on the books’s 25th anniversary) that describe part of my role in creating the book, followed by my thoughts on what I’m most fond of in regard to the book.

Fond memories of producing The SLB

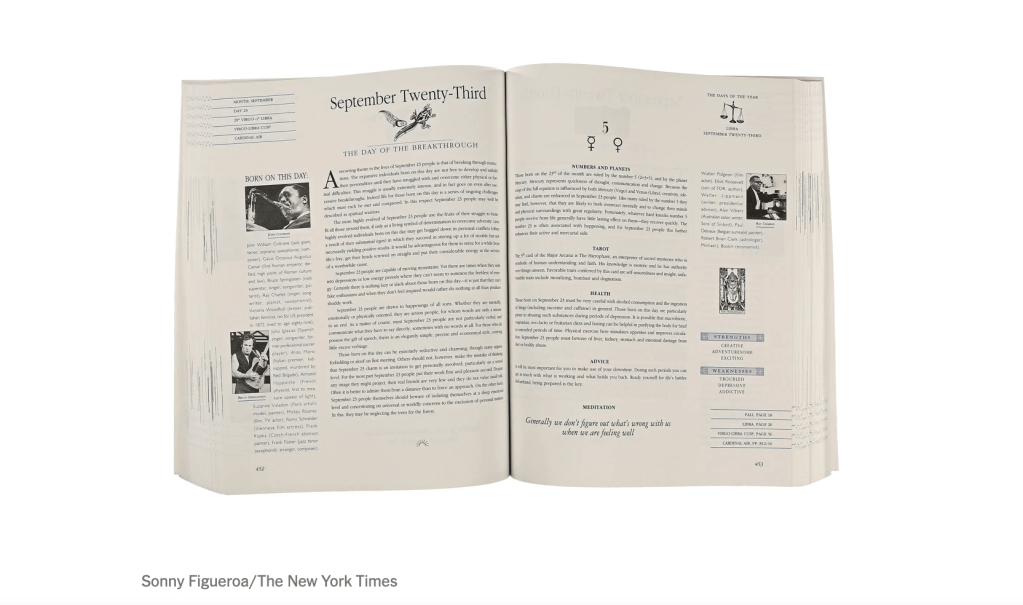

There are several things that I remember fondly about the publication of The Secret Language of Birthdays. First, the better part of a year that my father and I spent sweating in a small room, painstakingly going over the birthdays and achievements of the 7,320 notables (366 birthday 2-page spreads with a list of 20 notables per day). I feel proud that our lists were way ahead of their time in that they not only included great human diversity in the notables (and did not just pander to notables or trends currently popular) but also prominently featured many great and deserving women and non-white figures at or near the top of the list.

It was very liberating for us to be able to play God for a while and place heroes like the great saxophonist and composer John Coltrane atop a list, positioned above, for example, Bruce Springsteen, who was still in his heyday at the time (September 23, The Day of the Breakthrough, the page spread pictured in the NY Times photo above). This was a decision that we liked to think Bruce might agree with.

Second, I remember the great joy I had working at the Bettmann Archive choosing the photos that brought to life and illustrated the greatness, the fun, and the aforementioned diversity of each day of human achievement and personality. These photos gave the book a visual component that drew people in, as they could instantly relate to the prominent people born on their day, even if they did not formerly know who they were, and get the gist of the theme of the day. Because the criteria for including a notable’s photo in the book was based on visual splendor, how it fit the day, and what my father and I perceived as worthy achievement or cultural/historical importance rather than current fame, the book had a more classic, authoritative look that appears less dated today than it otherwise would.

Third, I am happy that for at least most days we were able to describe a personality that had a bit more depth (positives and negatives) than was usually described by astrology books of the time that engaged in platitudes or Pollyanna-like descriptions. It was my firm belief that if the book did not happen to hit with someone as accurately describing their own personality or that of a friend, at least if it described a more in-depth personality, they might still relate to it: just as readers relate to and see themselves in a novel’s character regardless of whether they would say that they resemble that character.

The last thing that I’m proud of in the creation of the book is that we were advanced a not huge sum of money by Penguin to produce the book ourselves, camera-ready for press. Together with a proficient assistant’s help, I sweated to meet the deadline, painstakingly laying out each page in the early publishing software Quark, which was a relatively new endeavor at the time. There were days when I lay awake at night, wondering whether we would make it. Then, finally, when the book’s layout was complete, my father and I, who both had desk-editing experience, went through the book with a fine-tooth comb. To this day, I am yet to have come across a single typo within its 832 pages, a rare achievement I would posit for a self-produced book of that size, especially in the realm of astrology.